Oral nucleoside antiviral is progressing toward future pandemic preparedness

May 23, 2024

Obeldesivir (GS-5245), a novel investigational small molecule oral antiviral, represents a new tool in the ongoing effort to prepare for future pandemics.

Several researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Gillings School of Global Public Health are co-authors of a new study published online May 22 by the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Dr. Timothy Sheahan (Photo by Megan May/UNC-Chapel Hill)

The study shares findings from an academic-corporate partnership between biopharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences and the Sheahan and Baric Labs at the Gillings School.

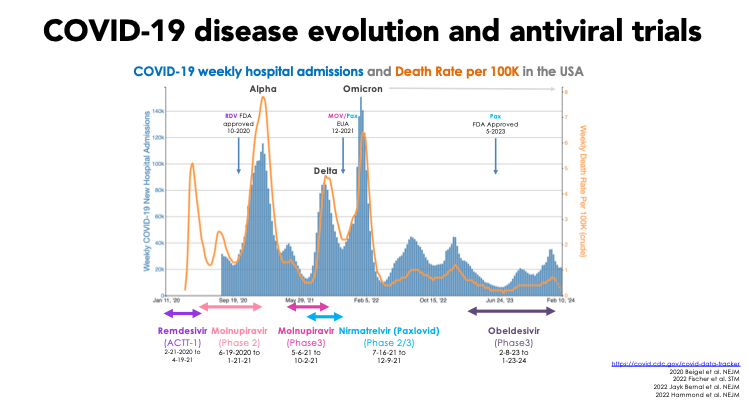

This is the same partnership that previously investigated remdesivir (sold under the brand name Veklury®). In 2020, remdesivir was authorized for emergency use and then fully approved during the COVID-19 pandemic. The drug works by stopping the SARS-CoV-2 virus from replicating. Remdesivir helps shorten time to recovery and reduces disease progression and mortality, but patients must visit a health care setting for IV administration.

Since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have been working on an oral antiviral drug of the parent nucleoside of remdesivir that could stop replication of the virus.

“Oral bioavailability means that you can take the medicine by mouth and do not need to visit a health care setting to receive treatment,” says Timothy Sheahan, PhD, an expert virologist and assistant professor of epidemiology at the Gillings School. “That is a potential limitation for remdesivir, which is an IV drug. With a prescription, you could take an oral antiviral at home just like you would take Tylenol.”

In the new study, oral obeldesivir was shown to reduce disease severity in mice infected with one of several different coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 (which causes COVID-19), SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Researchers observed a dose-dependent reduction in viral replication, weight loss, lung injury and loss of lung function.

In the new study, oral obeldesivir was shown to reduce disease severity in mice infected with one of several different coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 (which causes COVID-19), SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Researchers observed a dose-dependent reduction in viral replication, weight loss, lung injury and loss of lung function.

In addition, combining obeldesivir with the antiviral nirmatrelvir (an active component of Paxlovid) further improved outcomes in COVID-19-infected mice.

These results support further development of obeldesivir as a potential broadly effective anticoronaviral drug.

Gilead Sciences recently completed a Phase 3 clinical trial of the therapeutic in more than 2,000 people who tested positive for COVID-19 but did not have risk factors for developing more severe disease and were not hospitalized.

“While obeldesivir did not meet its primary clinical endpoint of reducing time to symptom alleviation in a standard risk population in the Phase 3 OAKTREE trial, it is a promising drug and no safety concerns were identified,” Sheahan says. “I think the issue is that currently, most people have stronger immunity to the virus that causes COVID-19 and the disease severity has greatly diminished since the pandemic. Early on, many people were ending up in the hospital and dying, which made the differences between placebo and treated groups stark and easily measurable. With obeldesivir, resarchers weren’t looking at prevention of hospitalization and death, but rather wanted to see how much it shortened the time for symptoms to resolve in people who are not at high risk for severe COVID-19. It’s harder to observe those subtler differences in the background of milder disease.”

Ultimately, the clinical trial assessed the safety profile of obeldesivir for use in a diverse population. Like remdesivir, obeldesivir could continue to be tested in humans for effectiveness and, if appropriate, rapidly deployed against susceptible novel coronaviruses that might emerge.

The research team also remains hopeful about the potential use of this broad-spectrum antiviral medicine against other RNA viruses.

The full list of co-authors on this study is: Fernando Moreira, Nicholas Catanzaro, Meghan Diefenbacher, Mark Zweigart, Kendra Gully, Ariane Brown, Lily Adams, Boyd Yount, Thomas Baric, Michael Mallory, Helen Conrad, Samantha May, Stephanie Dong, Trevor Scobey, Cameron Nguyen, Alexandra Schafer and Timothy Sheahan from the Department of Epidemiology at the Gillings School; Ralph Baric from the Gillings School’s Department of Epidemiology, the UNC Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and UNC’s Rapidly Emerging Antiviral Drug Development Initiative; David Martinez from the Department of Immunobiology and the Center for Infection and Immunity at the Yale School of Medicine; Gabriela De la Cruz from UNC’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center; Stephanie Montgomery from the UNC Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine; and Jason Perry, Darius Babusis, Kimberly Barrett, Anh-Hoa Nguyen, Anh-Quan Nguyen, Rao Kalla, Roy Bannister, Joy Feng, Tomas Cihlar, Richard Mackman and John P. Bilello from Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Contact the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health communications team at sphcomm@unc.edu.