The New Global Health Concentration

October 8, 2018

Working with ‘global’ populations in North Carolina and around the world

The word global in “UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health” is not incidental.

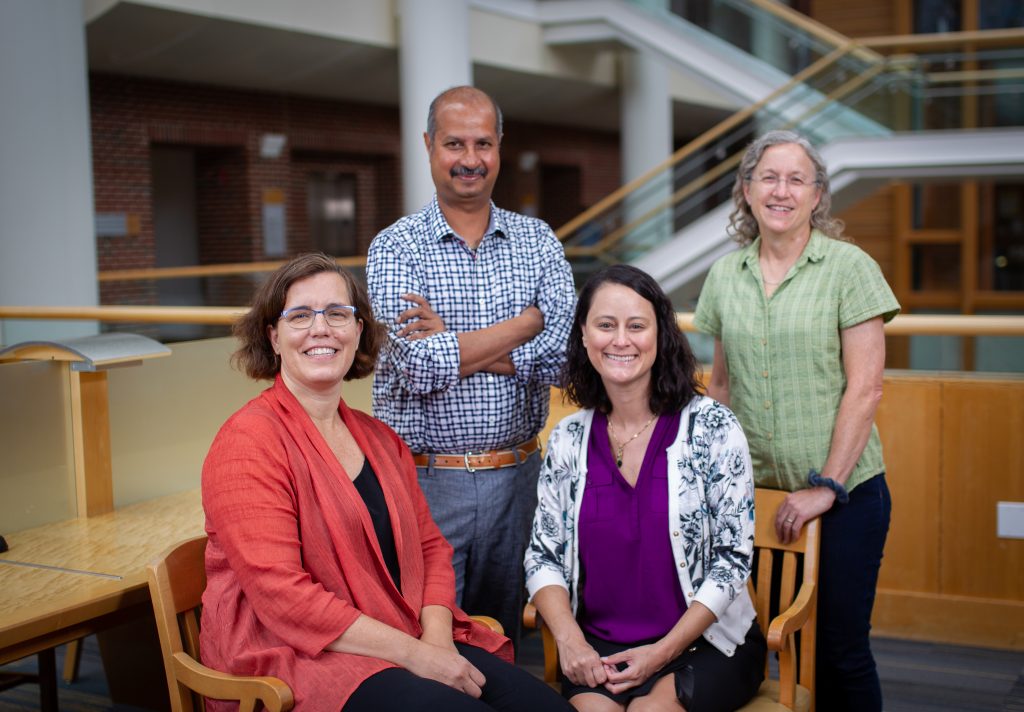

Left to right are Drs. Suzanne Maman, Rohit Ramaswamy, Jill Stewart and Ilene Speizer, co-leads for the global health concentration. Their disciplines – health behavior, leadership, environmental sciences and engineering, and maternal and child health, respectively – reflect the broad base of the concentration.

Since its earliest days, when faculty members traveled around the world to teach, collaborate and consult, the Gillings School’s focus has been on both local and global public health. The late Dan Okun, PhD, Kenan Distinguished Professor and chair of environmental sciences and engineering, reportedly worked in more than 90 countries. Students from around the world enrolled in UNC’s public health school.

Today, the Gillings School is in the vanguard of training students to solve global health problems, and our researchers and practitioners are leaders in public health efforts throughout the world. More than 80 of them work on projects that connect North Carolina to global communities.

The School is poised to continue its leadership through the newly designed global health concentration, set to be unveiled in fall 2019.

Peggy Bentley, PhD, Carla Smith Chamblee Distinguished Professor of Global Nutrition and associate dean for global health, was among the first people to recognize the intersection of North Carolina and the world, and she encouraged the School to adopt the phrase, “local is global.” By that, she meant that problems examined and solved in developing countries also may have application in rural North Carolina, and vice versa.

This perspective now is part of the revised global health competencies developed by an Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) committee on which Bentley served. In 2009, School leaders undertook a concerted effort to integrate global health content into courses throughout the curriculum. This was a major advance, one that many other Schools regarded as a good strategy.

“The global health concentration,” says Ilene Speizer, PhD, professor of maternal and child health and one of four co-leads for the new concentration, “creates a new set of courses, taught by faculty across several departments, which focus on global health in an integrated way.”

Developing that shared set of skills is at the heart of the school’s curriculum redesign.

Dr. Suzanne Maman

“This is part of a movement within the Gillings School to develop a more unified MPH program,” says Suzanne Maman, PhD, professor of health behavior and concentration lead. “It allows for a core set of integrated courses, which all students take, and then concentration-specific courses.”

The global health concentration models the importance of working across disciplines. Faculty members from diverse fields, whose work is global, have designed the concentration.

Maman, a social scientist trained in public heath, focuses on developing, implementing and evaluating HIV and intimate partner violence-prevention interventions in a variety of global settings, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa.

Speizer, who also works in sub-Saharan Africa, focuses on sexual and reproductive health issues among women, men and couples.

Jill Stewart, PhD, associate professor of environmental sciences and engineering, and Rohit Ramaswamy, PhD, professor in the Public Health Leadership Program and in maternal and child health, are also concentration co-leads.

Stewart seeks to understand environmental determinants of disease – and to understand and engineer solutions that ensure the health and well-being of local and global populations. Ramaswamy, who is trained in civil engineering, specializes in improving health systems in the United States, India, South Africa and Ghana.

While interdisciplinary training is key, Maman stresses that the curriculum is focused on providing students with skills they can apply in a variety of work settings.

“Our students will leave with skills in program planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation, using both qualitative and quantitative methods,” she says. “We know those skills will get our students jobs in which they can make an impact in any global environment.”

Ramaswamy says a unique quality of the Gillings School is that its faculty members are not only research leaders, but also leaders in the translation of research to practice.

“The global health concentration will help students put the skills into practice,” he says, “so that as graduating master’s students, they can make immediate impact in the world.”

Working on a global health project are (left to right) epidemiology student Charlotte Lane, Dr. Dilshad Jaff, health policy and management student Sheila Vipul Patel, Professor Sheila Leatherman and postdoctoral research associate Dr. Linda Tawfik.

An applied practical learning experience is part of the MPH curriculum, and the global health concentration faculty will help students leverage School connections with Triangle (N.C.)-based nongovernmental organizations dedicated to global health work, such as FHI 360, RTI International and IntraHealth. UNC’s strong presence in global public health – with longstanding partnerships in Malawi, Zambia, South Africa, Vietnam, China, Latin America and other areas – also provides opportunities for students to learn from researchers and practitioners, both in the classroom and through practicum projects.

Global health concentration graduates will just as likely be working in the United States as in global settings.

“We are as dedicated to populations in North Carolina as we are to populations in Africa,” says Ramaswamy. “When we talk about global public health, it’s important to understand that this is not just for students who want to work outside the U.S. The things we teach will be of great value to students who want to work with immigrant, refugee and vulnerable populations in the U.S.”

“Preparing students to treat and prevent diseases worldwide is necessary to ensure healthy populations at home,” says Stewart. “Health threats such as emerging diseases and the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance require us all to think and act on a global scale.”

Maman is thrilled by the School’s commitment to raise the profile of its global health training.

“We’re going to develop an incredible skill set among cohorts of trained MPH professionals who then will have great careers, through which they will have an impact on global health at all levels,” she says. “Our students will work with global populations here in the U.S. and throughout the world, in research, practice and policy, and in settings ranging from community organizations to ministries of public health.”

—Michele Lynn

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.