Public Health Data Science

October 8, 2018

A skill set much in demand

In virtually all major sectors of the global economy, employers large and small – from Google and the Gates Foundation to local startups – are clamoring for credentialed data scientists.

In virtually all major sectors of the global economy, employers large and small – from Google and the Gates Foundation to local startups – are clamoring for credentialed data scientists.

“I don’t think there are many employers out there who are not in need of this skill set right now,” says Lisa LaVange, PhD, professor and associate chair of biostatistics at UNC’s Gillings School of Global Public Health. LaVange oversees the new Public Health Data Science concentration, scheduled to become part of the Gillings School’s MPH program in 2019.

Until last year, LaVange directed the Office of Biostatistics in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and in that role, had to face the data science skills shortage herself.

“More than 200 statistics reviewers worked for me at FDA, most of them with PhDs, but it wasn’t enough,” she says. “We needed more data scientists, because there are more data now, and so many questions we need to ask of the data.”

Health-focused organizations always have needed experts in statistics and computation, but in the age of the internet, as data gathering has become ubiquitous, this need intensified. Data sets from traditional sources, such as clinical trials and population studies, are becoming larger and more complex. Many new, nontraditional sources of data exist, including electronic health records, patient registries, insurance claims databases, clinical genomic databases, even internet browsing histories and search-term trends.

Dr. Lisa LaVange

“We’re now in a world where everyone’s data are out there, one way or another,” LaVange says.

Health professionals are attempting to learn more from these data – for example, by running virtual clinical trials on integrated sets of insurance claims databases or by gathering and analyzing disease-outbreak data and broadcasting the results in real-time to clinicians or epidemiologists with mobile apps.

Moreover, the new emphasis on very large databases, distributed computing power and artificial intelligence (AI)-related analytical techniques has drawn a new type of organization – the “big tech” company – into the public health space. Google, Microsoft and Amazon all have major public health-related projects in the works.

A key problem for those wanting to make use of the new Niagara of health data is that it is often less filtered, less “clean,” than traditional health data.

“You want to make inferences from some of these enormous data sets as if they were carefully collected and curated data from well-designed studies, but usually they’re not,” LaVange says.

Drawing useful conclusions from such data may be possible only with cutting-edge analytical approaches – thus, the enormous demand for data scientists trained in the latest methods. LaVange and her Gillings School colleagues aim to give that training to students who join the Public Health Data Science MPH program. (See sph.unc.edu/mph-data-science.)

Data science is a mix of computer science, statistics and applied math tools, so incoming students will have majored or had some undergraduate coursework in those areas.

“They should know linear algebra and calculus, and have some computer science exposure, although we’ll teach programming languages and coding in our program,” LaVange says.

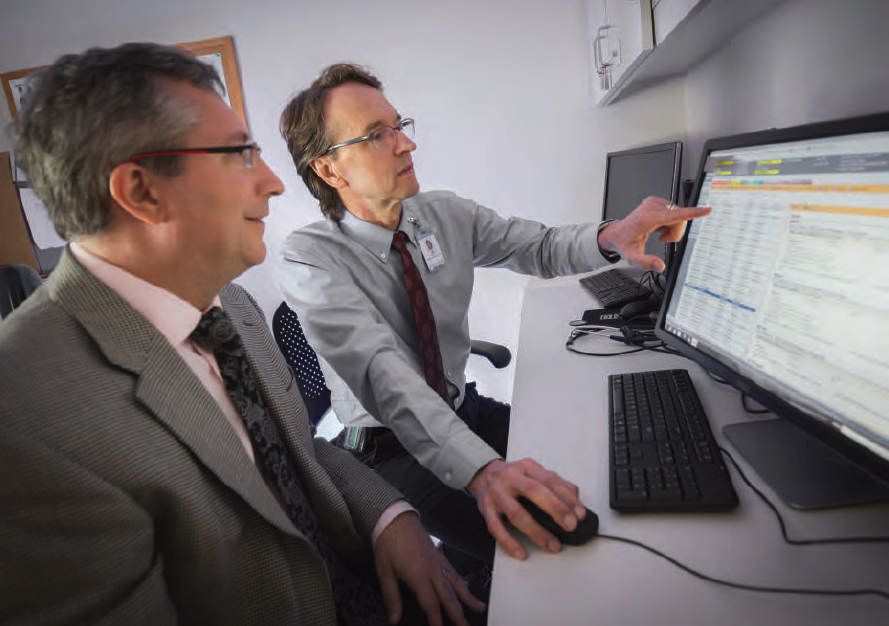

Dr. Michael Kosorok (foreground) discusses precision medicine strategies with Dr. George Retsch-Bogart, a pediatric pulmonologist at the UNC School of Medicine. Precision medicine is one application of data science and machine learning methods that are the focus of the new Public Health Data Science concentration.

Biostatistics chair Michael Kosorok, PhD, W.R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor, is an internationally recognized expert on machine learning, and the program includes a course focused on that. Other coursework covers probability and statistical inference, experimental design, epidemiology, and advanced data-mining and statistical analysis.

“One thing we’ll include that generally isn’t found in data science degree programs outside the health field is a familiarity with public health-related databases,” LaVange says. “Because the epidemiology department is working with us in developing the data science curriculum, for example, we are able to tap their tremendous expertise with Medicare and other claims data, and that will be a terrific benefit for the students.”

Despite the health focus, participants in the program should emerge from it with the skills they need to be successful job candidates in Silicon Valley, on Wall Street or in Washington, D.C. – wherever data need mining and processing. LaVange expects, though, that most will want to use their newfound knowledge to improve public health.

“We will get them excited about public health problems to which they can apply their skills,” she says. “They’ll be able to go on to do great things with these skills – from finding new ways to monitor and measure public health to finding cures for diseases.”

—Jim Schnabel

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.