Perspectives on the flu: Ralph Baric, PhD

May 15, 2018

Q: How bad could the next pandemic be, in terms of number of people who die?

Q: How bad could the next pandemic be, in terms of number of people who die?

A: The 1918 flu in the United States had attack rates of 30 to 40 percent, which means it infected that proportion of people who had no prior immunity. For those infected, mortality rates were up to 3 percent. If the next flu pandemic is equally serious, then in the United States alone, more than 100 million people would be infected, and more than 3 million would die. That would be in the first wave of the pandemic – a few months. The 1918 flu had at least three waves over one year’s time, starting in spring 1918.

Q: Why was the 1918 flu so deadly?

A: It was an H1N1 strain, so-called for the variants of hemagglutinin (H) protein and neuraminidase (N) protein on the viral surface, and the population hadn’t been exposed to an H1 strain in a very long time. When those new hemagglutinin types come through, and people don’t appreciate how dangerous they are, the mortality rates tend to go up. With 1918 flu, a combination of viral gene variants also made the flu more deadly.

Dr. Ralph Baric (Photo by Linda Kastleman)

Q: Where would you expect the next big flu pandemic to emerge?

A: Most likely, it would emerge in a dense population with open animal markets – for example, markets with chickens, ducks and geese in close proximity to people. Such environments raise the risk that a flu strain adapted to animals will adapt to infect humans, and because it will be new, we’ll have little or no immunity to it.

Q: Is the U.S. health care system ready for something like this?

A: There are about 4,700 hospitals in the country. Most are set up to provide critical care to no more than 20–40 people – making the total critical care capacity in the country on the order of hundreds of thousands of patients. However, a pandemic similar to the 1918 flu would produce millions, or even tens of millions, of critically ill people. That gives us an idea of how overwhelmed the system would be.

Q: What about antiviral drugs, such as Tamiflu?

A: The government has stockpiled anti-flu drugs, and in principle, the drugs would be administered to health care workers and some patients. Those stockpiles would be depleted rapidly, and there probably wouldn’t be enough available to treat millions of patients. Also, while those drugs in clinical trials have seemed effective if given early, before symptoms appear, there haven’t been trials showing that they work for people who are already seriously ill.

Q: What about the seasonal vaccine?

A: The seasonal flu vaccine is designed to be reformulated quickly to include protection against new strains. If a new pandemic strain were to emerge, we almost immediately would identify the strain and begin testing candidate vaccines against it – but that process of vaccine testing and large-scale manufacture takes months, so it’s unlikely a vaccine would be available during the first wave of the pandemic.

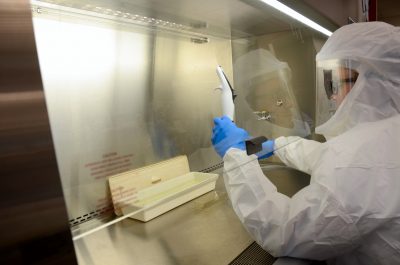

Dr. Timothy Sheahan wears a full-body protective suit while working in Dr. Ralph Baric’s biosafety level four lab. (Photo by Jennie Saia)

Q: So, against a first wave of a highly virulent pandemic flu, we’d be largely defenseless?

A: A universal vaccine could protect us from future flu pandemics, but such a vaccine hasn’t been developed yet. That’s still probably five to 10 years away.

In a worst-case scenario, there isn’t a whole lot we could do to stop a flu pandemic. It would sweep through the population, and people would die more quickly than they could be buried. Even people who weren’t sick wouldn’t go to work; the economy would come to a standstill. Countries would quarantine their borders, so international trade would collapse. There would be societal upheaval. Remember, too – America is a relatively rich and well developed country. The situation would be far worse in most other parts of the world.

Q: Is it conceivable that a future pandemic flu strain could have an even higher mortality rate than the 1918 flu?

A: There are bird flu strains now that sporadically infect humans with mortality rates as high as 50 percent. Most virologists think that to be highly transmissible among humans, a flu virus can’t be that virulent. Yet, if there were a highly transmissible strain with mortality rates even close to that level, then obviously, we would be talking about billions of deaths. You’d be remodeling the human population.

Ralph Baric, PhD, is professor of epidemiology at the Gillings School and professor of microbiology and immunology at the UNC School of Medicine. He studies dangerous emergent viruses, including SARS, MERS, Ebola, Zika and pandemic influenza.

—Jim Schnabel

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.