NC Medicaid data show progress in state's opioid epidemic, but patients need better access to treatment

November 19, 2019

A new analysis of North Carolina Medicaid data finds that, while important progress is being made in combating the state’s opioid epidemic, more work is needed to increase the rate at which Medicaid enrollees diagnosed with Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) receive effective medications to treat it. The research is summarized in a Health Affairs blog published today.

The study was conducted by researchers at Duke University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with support from Arnold Ventures. The resulting white paper and data supplement, which presents information at the county level, identified some encouraging trends in the North Carolina Medicaid population. For example, fewer Medicaid enrollees are using prescription opioids overall. Additionally, fewer enrollees are receiving prescription opioids in combination with other medications that are known to increase risk of adverse health outcomes.

Importantly, the rate of opioid overdoses also has declined.

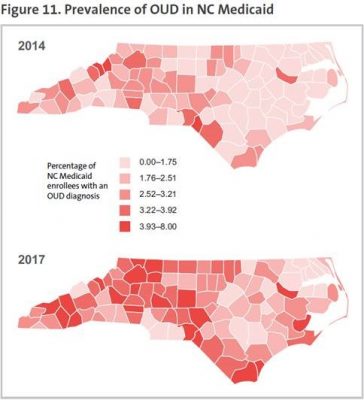

However, according to the researchers, the number of Medicaid enrollees with a reported diagnosis of OUD increased from just over 27,000 in 2013-2014 (representing around 1% of the study population) to over 45,000 by 2017-2018 (or nearly 2% of the study population). This growth is cause for concern, but may also reflect a positive trend of clinicians increasingly identifying and addressing OUD.

However, according to the researchers, the number of Medicaid enrollees with a reported diagnosis of OUD increased from just over 27,000 in 2013-2014 (representing around 1% of the study population) to over 45,000 by 2017-2018 (or nearly 2% of the study population). This growth is cause for concern, but may also reflect a positive trend of clinicians increasingly identifying and addressing OUD.

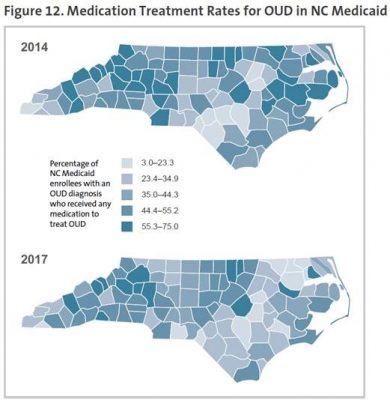

During this same time period, the number of Medicaid enrollees receiving medications to treat OUD increased significantly. Unfortunately, the treatment rate has not kept up with the rising number of people who have OUD. While more people were receiving treatment in 2017 versus 2014, the treatment rate itself actually declined slightly.

“Overall, we are seeing important improvements in the number of Medicaid enrollees with OUD who receive treatment, reflecting significant federal and state investments in this area. However, the rate of growth of OUD in the population is outpacing the treatment rate,” said Principal Investigator Aaron McKethan, PhD, a core faculty member at Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy and adjunct professor of population health sciences at the Duke University School of Medicine.

The scientific literature (PDF) indicates that people with OUD have better outcomes if medication therapy is ongoing and long-term. However, according to Alex Gertner, a doctoral candidate in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, “Roughly half of N.C. Medicaid enrollees who initiate buprenorphine therapy for OUD remain on therapy for six months or more, suggesting that even the patients who get treatment face challenges to staying on it.” (Gertner works closely with Marisa Elena Domino, PhD, a research fellow and principal investigator with UNC’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research and professor of health policy and management at the Gillings School).

Alex Gertner

Dr. Marisa Domino

Nationally, retention rates among people receiving medications to treat OUD are generally quite low, and relapse is a recognized part of the disease and recovery process. The fact that half of N.C. Medicaid enrollees with OUD who initiate medication treatment remain on the medication for at least six months can be viewed as positive compared to national benchmarks. On the other hand, it likely means that less than half of treated enrollees receive continuous treatment for long enough to produce the best clinical benefits. Clearly, more work is needed to close these gaps.

This study focused only on the state’s Medicaid program, which covers health care for more than 2 million low-income adults, children, pregnant women, elderly adults and people with disabilities throughout the state.

“To put these Medicaid findings in context, in North Carolina, about half of people coming to the emergency department for opioid-related overdoses are uninsured (PDF) or self-pay,” says McKethan. “Only 20% of uninsured/self-pay individuals with OUD have received outpatient treatment for their addiction in the past year, which is about half the Medicaid rate. To be sure, Medicaid is an important medical safety net that is crucial in the ongoing fight against the opioid epidemic throughout North Carolina.”

The Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy works to improve health and the value of health care through practical, innovative and evidence-based policy solutions. To learn more, visit healthpolicy.duke.edu.

The Duke School of Medicine Department of Population Health Sciences’ mission is to produce important insights, guide them into practice and prepare the next population health scientists well to improve the health of communities everywhere. Learn more at populationhealth.duke.edu/

The UNC Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research seeks to improve the health of individuals, families and populations by understanding the problems, issues and alternatives in the design and delivery of health care services. This is accomplished through an interdisciplinary program of research, consultation, technical assistance and training that focuses on timely and policy-relevant questions concerning the accessibility, adequacy, organization, cost and effectiveness of health care services and the dissemination of this information to policy makers and the general public. To learn more, visit www.shepscenter.unc.edu/.

CONTACT:

Lindsay McCall, MPH, UNC Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research

Office: (919) 966-8628 (o)

Cell: (919) 418-3413

lmccall@email.unc.edu

Contact the Gillings School of Global Public Health communications team at sphcomm@unc.edu.