Marketing ban tackles TV ads for unhealthy foods in Chile

June 1, 2023

Chilean policies aimed at reining in unhealthy food marketing are succeeding in protecting children from the onslaught of television advertisements (TV ads) for these products, according to new research published in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity.

A child watches junk food advertising on television.

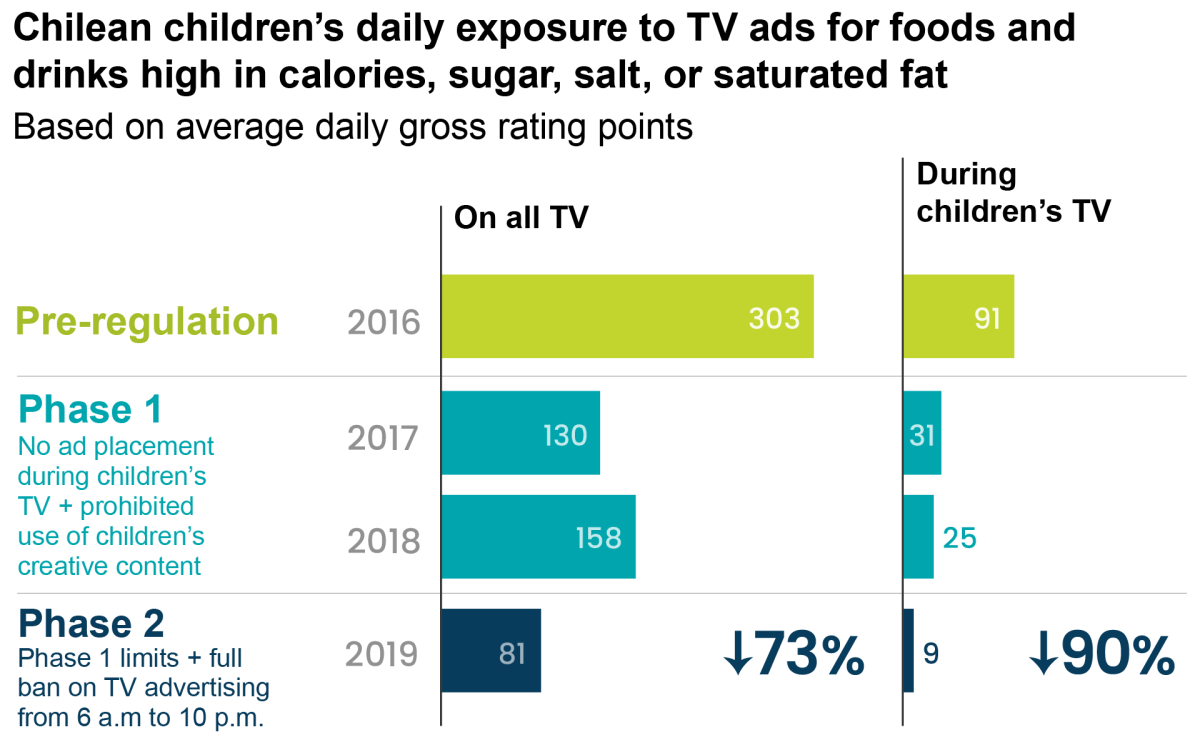

The country’s multi-phased regulations, which were introduced in 2016, led to a 73% drop in children’s exposure to TV ads for regulated foods and drinks — those that exceed legal thresholds for calories, sugar, salt or saturated fat — by 2019.

During this time, the number of ads for unhealthy foods dropped 64% during all TV programs and 77% during children’s programming. Researchers also found that 67% fewer unhealthy food ads used child-directed creative content such as cartoons, characters, toys or contests, which are also prohibited under the country’s laws.

These and other findings from researchers at the University of Chile, Diego Portales University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill underscore both the potential and need for strict rules around marketing to build healthier eating habits.

The study also highlights the importance of a key policy addition that contributed to the regulations’ success: The initial Law of Food Labeling and Advertising in 2016 limited child-directed creative content in any marketing and prohibited companies from placing TV ads for regulated products during programs attracting a child audience. In 2018, Chile extended this prohibition to a full “daytime” ban across all TV from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m.

While researchers saw a decline in advertising for unhealthy foods during earlier phases of the law (in 2017 and early 2018), the significantly greater drop following the full daytime ban is noteworthy.

Dr. Francesca Dillman Carpentier

“Focusing on child-directed ad content and child-directed programming to reduce children’s exposure to unhealthy food advertising does work to an extent, based on what we’ve seen in Chile, but children are simply exposed to much more than this,” said Francesca Dillman Carpentier, PhD, W. Horace Carter Distinguished Professor at the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media and the study’s first author. “To markedly reduce the amount of unhealthy food promotions children view, we see that it takes a bold move like Chile’s 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. ban to be effective. The number of unhealthy food ads on TV, as well as kids’ exposure to them, was greatly reduced after Chile added the daytime ban on these ads.”

This study’s findings underscore a weakness of nearly all governmental restrictions on TV advertising for unhealthy foods worldwide: Most focus on very narrow windows of time or programming, leaving children exposed most of the day and night to targeted ads for unhealthy foods and drinks. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This study provides evidence that countries could significantly strengthen existing policies by expanding TV restrictions to complete bans. Countries considering introducing policies to regulate food marketing can also learn from the Chilean experience to protect children more effectively from ad exposure.

Chile enacted these marketing controls in 2016 as part of an ambitious, comprehensive policy package aimed at reducing childhood obesity and other health risks by creating a healthier food environment. The Law of Food Labeling and Advertising also mandated “stop sign” warning labels on packages for unhealthy foods and banned their sale or promotion in schools.

Chile’s approach remains one of the most ambitious regulatory frameworks in the world aimed at tackling rising nutrition-related diseases and soaring health care costs, and many policymakers and public health advocates worldwide have been watching to gauge the policy package’s effectiveness.

Other studies evaluating the combined effects of Chile’s marketing restrictions, warning labels and school ban have yielded similarly promising results: A study of household grocery purchases found a 24% drop in calories purchased in the first year (during the most lax period of the law’s three-phased nutritional criteria) and a 37% reduction in sodium purchased. Focus groups indicate that parents are being encouraged by their children to avoid buying foods with warning labels. Students reduced their sugar, saturated fat and sodium intake in schools — albeit with some evidence of compensation outside of school settings. And marketing restrictions also led to the reduction of child-directed marketing strategies from being used by nearly 50% of breakfast cereals to just 15% in the first year of the law.

Dr. Lindsey Smith Taillie

“The Chilean experience has shown us that rigorous food marketing regulations work to reduce kids’ exposure to TV food advertising,” said co-author Lindsey Smith Taillie, PhD, associate professor and associate chair of academics in the Department of Nutrition at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Gillings Global School of Public Health. “Looking to the future, we need to figure out how to monitor and regulate the digital food marketing environment as kids increasingly shift their attention to smartphones and other online content.”

Contact the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health communications team at sphcomm@unc.edu.