Lab-grown mini-lungs mimic the real thing — including COVID-19 infection

October 23, 2020

A team of researchers at Duke University has developed a lab-grown living lung model that mimics the tiny air sacs of the lungs where coronavirus infection and serious lung damage take place. This advance has enabled them to watch the battle between the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and lung cells at the finest molecular scale.

Dr. Ralph Baric

Caitlin Edwards

Their work is outlined in a new study published online October 21 by the journal Cell Stem Cell, which describes the development of the mini-lungs and some early experiments with coronavirus infection. Paper co-authors include two researchers from the UNC-Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health: Caitlin Edwards, MS, is a research specialist in the lab of Ralph Baric, PhD, William R. Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor of epidemiology, professor of microbiology and immunology, and global authority on coronaviruses.

The novel coronavirus damages delicate, balloon-like air sacs in the lungs, known as alveoli, which can lead to pneumonia and acute respiratory distress — the leading cause of death in COVID-19 patients. Scientists have been hampered in COVID-19 studies, however, by the lack of experimental models that mimic human lung tissues.

In response, a team led by Duke cell biologist Purushothama Rao Tata, PhD, developed a model using “lung organoids,” also dubbed mini-lungs in a dish. The organoids are grown from alveolar epithelial type-2 cells (AT2s) which are the stem cells that repair the deepest portions of the lungs where SARS-CoV-2 attacks.

Earlier research at Duke had shown that just one AT2 cell, isolated into a tiny dish, could multiply to produce millions of cells that assemble themselves into balloon-like organoids that look just like alveoli. However, the “soup” in which the cells were grown contained complex ingredients such as a serum from cows that is not completely defined.

Tata’s group took on the challenge of predicting and testing many combinations of chemically pure factors that would do the job just as well —the result is a purely human organoid without any helper cells.

Mini-lungs grown in tiny wells will enable high throughput science, in which hundreds of experiments can be run simultaneously to screen for new drug candidates or to identify self-defense chemicals produced by lung cells in response to infection.

“This is a versatile model system that allows us to study not only SARS-CoV-2, but any respiratory virus that targets these cells, including influenza,” Tata said.

In using mini-lungs to study SARS-CoV-2 infection, Tata’s team collaborated with virology colleagues at Duke and UNC’s Gillings School. To safely handle these deadly viruses, the researchers utilized state-of-the art biosafety level 3 facilities to infect lung organoids. The researchers watched the gene activity and chemical signals that are produced by the lung cells after infection.

“This is a major breakthrough for the field, because we were using cells that didn’t have purified cultures,” said Baric. The Duke mini-lungs are 100% human with no supporting cells that could confuse findings. “This is incredibly elegant work to figure out how to purify and grow AT2 cells in culture in pure form.”

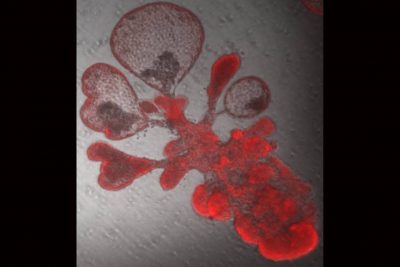

A single lung stem cell copied itself to generate thousands of cells and form a bubble-like structure that resembles breathing tissues of the human lung. These are the cells that the SARS-CoV-2 virus targets. (Image credit: Arvind Konkimalla/Tata Lab)

Researchers in the Baric Lab are capable of changing any nucleotide of the COVID-19 virus’s genetic code at will, so they produced a glowing version that would reveal where it traveled in the mini-lungs. They confirmed that it did indeed home in on the crucial ACE2 cell surface receptor, leading to infection.

Once infected with the virus, the organoids were shown to launch an inflammatory response mediated by interferons. The researchers also witnessed the cytokine storm of immune molecules human lungs typically launch in response to the virus.

“It was thought cytokine storm happened due to the large influx of immune cells, but we can see it also happens in the lung stem cells themselves,” Tata said.

Tata’s lab found that the cells also produced interferons and experienced self-destructive cell death, just as samples from COVID-19 patients have shown. The signal for cell suicide was sometimes triggered in uninfected neighboring lung cells as well, as the cells struggled to get ahead of the virus. The researchers compared the gene activity patterns between the mini-lungs and samples from six patients with severe COVID-19 and found they agreed with “striking similarity.”

“We’ve only been able to see this from autopsies until now,” Tata said. “Now, we have a way to figure out how to energize the cells to fight against this deadly virus.”

In another series of experiments, mini-lungs treated with low doses of interferons before infection were able to slow viral copying. Suppressing interferon activity before infection, however, led to increased viral replication.

Tata, who is a part of Duke’s regenerative medicine initiative, Regeneration Next, said his lab was working on growing the mini-lungs in 2019 and had achieved a working model just as the coronavirus pandemic emerged. His group will work with both academic and industry partners to use these cells for cell-based therapies and, eventually, to try to grow a complete lung for transplantation.

Baric said his lab will probably use the mini-lungs to better understand a new strain of SARS-CoV-2 called D614G that has become the dominant version of the virus. This strain, which emerged in Italy, has a spike protein that is apparently more efficient at recognizing the ACE2 receptor on lung cells, making it even more infectious.

This research was performed with support from the Chan Zuckerberg Foundation, the United States National Institutes of Health (UC6-AI058607, AI132178, AI149644, R00HL127181, R01HL146557, R01HL153375, R21GM1311279, F30HL143911, DK065988), Duke University and United Therapeutics Corporation.

This story was first published by Duke Today.

Contact the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health communications team at sphcomm@unc.edu.