Gillings students propose framework for addressing health disparities in US maternal mortality

October 1, 2021

A group of five Master of Public Health (MPH) students at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health has co-authored a new publication that creates a model for understanding and addressing determinants that contribute to maternal mortality in the United States.

Published in Harvard Public Health Review, the paper gives a comprehensive overview of the complex biological, social and environmental factors that make the U.S. the only wealthy country in the world in which mothers and birthing parents are dying at a higher rate than 25 years ago.

The five co-authors are students or recent alumnae of the Population Health for Clinicians MPH concentration, a collaboration between the Gillings School and the UNC School of Medicine that offers interdisciplinary public health and population health training to current and future health care providers. Melissa Hill, MPH (2021), Jaclyn Tremont, MD, Michelle McCraw, MPH (2021), Natalie Spach, MPH (2021), and Anne Berry, MD, collaborated on the paper while in the “Understanding Public Health Issues” course taught by Jon Hussey, PhD, assistant professor of maternal and child health.

Dr. Anne Berry

“Many people view maternal health as prenatal care – and access to good quality care is an important part of that,” Berry explained. “But when you really look at health disparities in maternal health outcomes, many of them occur before a person ever becomes pregnant. We have to look over the entire course of life to address the factors that contribute to someone having a healthy pregnancy.”

Social determinants of health, such as education, income, location and environment, play a major role in pregnancy health outcomes. When compounded with existing systems of racism and health inequity, these determinants place people who give birth at major risk of otherwise preventable death – particularly Black and American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) people, who are disproportionately at risk.

The research team identified four major categories of risk factors:

- Biological and genetic – many pregnancies are complicated by pre-existing or chronic health conditions, most significantly cardiovascular and heart diseases. Genetic risk factors for these conditions must be considered in the context of a person’s environment.

- Behavioral and psychosocial – access to care can be limited or delayed based on many social and psychological factors, such as family support, documentation status or risk of intimate partner violence. Inability to access care can also impact the management of chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension, which, if left untreated, can have adverse effects on a pregnancy. People who are Black, Hispanic or Asian/Pacific Islander are often at higher risk of these conditions.

- Environmental – Where a person lives can impact their access to quality health care, nutritious food and a safe living environment. Communities that are non-white, rural or of lower income bear a disproportionate burden of these environmental risks, which can significantly affect pregnancy outcomes.

- Social, political and economic – Structural racism has created a complex set of factors that have had a disproportionately negative effect on health outcomes, especially for Black mothers and birthing parents. In addition to bearing the highest burden of maternal mortality, Black people are less likely to be adequately insured, are more likely to encounter provider bias, receive lower-quality care and experience stress than their white counterparts. Black college-educated women have worse maternal health outcomes than white women who do not have a high school diploma.

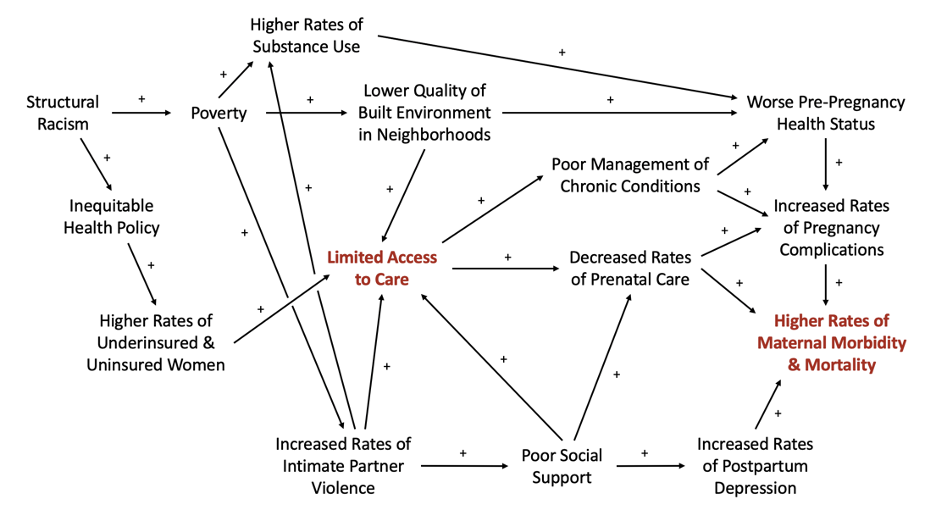

Using this research, the team developed a model for understanding the complex system of inequities that contribute to maternal mortality in the U.S. and outlined a set of priorities that public health leaders should consider when designing future interventions. Such priorities should address access to care, quality of care and maternal support programs.

Causal loop diagram depicting select determinants of maternal mortality in the U.S.

“Support for public health policy that encourages women to seek preventative screenings, low-cost medications and disease education in universally understandable terms is necessary,” they wrote. “However, the responsibility to combat increasing rates of maternal mortality cannot fall to those patients most affected by it – namely communities with higher baseline risk due to racism and other complex medical, environmental and social factors. Federal, state and local policymakers must partner with clinicians and communities to guarantee protections for vulnerable patients.”

“What we found points to the necessity of strengthening health care and health promotions systems, particularly for people of color, during the pregnancy, birth and postpartum periods, as well as before a person ever becomes pregnant,” said Barry. “And not just health care itself – things like access to healthy foods, safe communities and spaces for physical activity are all necessary pieces of the goal. Safe and healthy pregnancy and birth are long-term projects, and we can’t achieve them if we only start when people get pregnant.”

Among programs that might improve maternal health outcomes, the team suggested programs that integrate community health workers, doulas and other support groups. Structural barriers that affect quality and access of care must be addressed, but these community-based services can play a critical role in providing education and tools to mitigate the impact of social determinants on maternal health and disrupt the barriers of systemic racism that prevent people who give birth from accessing quality care.

Contact the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health communications team at sphcomm@unc.edu.