Evidence, ethics and human rights should shape policies related to migration and health

November 10, 2017

More people are of migrant or refugee status now than at any other time in history, and the health of these vulnerable populations has become a critical public health issue. Their legal status – including lack of documentation and lack of access to screening – makes many of them susceptible not only to illness but to stigmatization and discrimination.

These issues are addressed in a new article in the International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, co-authored by Dilshad Jaff, MD, MPH, adjunct assistant professor of maternal and child health at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and program coordinator for solutions to complex emergencies in the School’s Research, Innovation and Global Solutions unit. The article, which aims to provide new perspectives on the challenges of migrant health, traces a common migration route from Africa to Europe to illustrate ways the health needs of migrating people can be met.

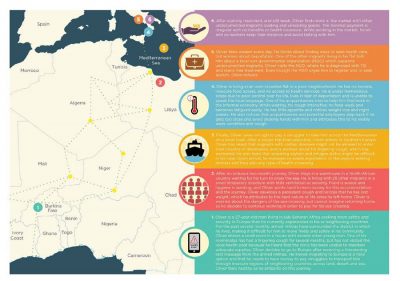

This map illustrates the representative journey of a young man migrating from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe.

Jaff and his co-authors use a map loosely derived from Patrick Kingsley’s book, The New Odyssey (Liveright, 2017) to trace the journey of a typical 27-year-old man in sub-Saharan Africa as he makes his way to central Europe under threat of political violence. At each stage, the authors identify situations in which human rights and ethical values are affected in relation to TB care. The migrant’s experiences include long sea and overland travel, crowded living conditions, and lack of food, shelter, income and health services.

The illustration provides the basis for discussing TB and migration from the perspective of human rights, with a focus on the right to health.

The authors acknowledge the challenges in trying to provide health services to migrants, especially in countries where nationalism takes precedence over human rights concerns. They encourage TB programs and practitioners to build alliances with migrants’ rights movements and others working toward global health justice.

“Aligned with others,” they write, “TB programs can become spaces where alternatives to stigmatizing, de-humanizing and rights-denying approaches to migrant health are tried and shown to succeed. Cross-border projects…can…reaffirm the insight of global health ethics – that health for all is a shared project, and that responsibility increases with the privilege, wealth and advantages that a country holds.”

Jaff noted that decades of violence, oppression, discrimination, deprivation, injustice and human rights abuses in their home countries are leading migrants to suffer poor health outcomes.

“By adopting rational public health and human rights approaches to the problem, migrants will be able to confront the challenges they face,” he said.

Other co-authors are Verina Wild, of Ludwig-Maximilians University, in Munich; N.S. Shah, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta; and Mike Frick, of the Treatment Action Group, in New York, N.Y.

Gillings School of Global Public Health contact: David Pesci, director of communications, (919) 962-2600 or dpesci@unc.edu