Eating for two: Changing the mother’s diet as an intervention for prenatal arsenic exposure

Jeliyah Clark, UNC-Chapel Hill, Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering

Graduate trainee, UNC SRP Project 2 and Project 3

Jeliyah Clark, PhD candidate

Pregnancy is a magical time for an expecting mother, yet there are many aspects to consider when you’re eating for two.

During the first weeks of pregnancy, finger-like projections emerge from a ball of cells that will go on to become the embryo. These finger-like projections invade the wall of the uterus to form the placenta, connecting the baby’s umbilical cord to the mother’s blood supply. This process is called placental invasion, and when done properly, it allows for the transfer of nutrients and promotes fetal growth.

The placenta is a double-edged sword, also transferring toxic chemicals circulating in the mother’s blood. My research centers on reducing fetal exposure to a particularly toxic chemical: arsenic.

Arsenic is a carcinogen that can be ingested through contaminated drinking water. It’s known as both the “king of poisons” and the “poison of kings,” because it’s been implicated in murders throughout the Middle Ages. More recently, several studies have linked maternal arsenic exposure to lower birth weight, which is concerning because low birth weight is associated with infant mortality and heart disease in adulthood.

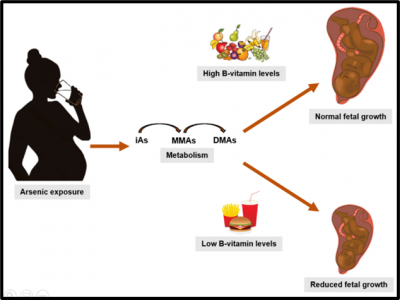

Arsenic may hinder placental invasion and disrupts other processes critical to fetal growth. Interestingly, arsenic metabolism relies on folate and other B-vitamins we typically consume in our diets. Among adults, supplementing diets with B-vitamins improves the body’s ability to eliminate this toxic chemical and protects against arsenic-induced disease.

Globally, nearly 200 million people are exposed to arsenic in contaminated drinking water, including in North Carolina where arsenic has been measured in water at levels exceeding government regulations. Most countries with high arsenic contamination of drinking water also suffer from widespread B-vitamin deficiencies. My research aims to investigate a potential solution and has global implications for the dietary recommendations made to pregnant women.

Globally, nearly 200 million people are exposed to arsenic in contaminated drinking water, including in North Carolina where arsenic has been measured in water at levels exceeding government regulations. Most countries with high arsenic contamination of drinking water also suffer from widespread B-vitamin deficiencies. My research aims to investigate a potential solution and has global implications for the dietary recommendations made to pregnant women.

To achieve this, I will use a unique dataset collected from women who were exposed to arsenic contaminated drinking water while pregnant to evaluate whether B-vitamins also protect the developing fetus from the harms of arsenic exposure. With statistical modeling approaches, I will test whether the negative relationship between the levels of arsenic measured in the mothers’ bodies and infant birth weight are attenuated – or completely eliminated – by higher B-vitamin levels measured in the mother’s blood.

Findings from this work could demonstrate that consuming multivitamins or eating foods high in B-vitamins during pregnancy may protect developing babies from prenatal arsenic exposure. In fact, it just might provide a new meaning to the phrase “eating for two.”