What should we do about the opioid crisis?

October 15, 2017

Nabarun Dasgupta, PhD

Senior research scientist

UNC Injury Prevention Research Center and UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy

Stephen Marshall, PhD

Professor of epidemiology

Director, UNC Injury Prevention Research Center

First and most importantly, we should improve our understanding of the conditions that lead to chronic pain and addiction, compelling us to do something about those conditions. Working within our health-care delivery system, we must embark immediately upon implementing specific changes with existing tools. To make these improvements enduring, we must acknowledge the racial bias that pervades our response to the crisis.

Q: How can we better understand the situations that gave rise to the epidemic?

A: Our understanding of the opioid crisis is hampered by inadequate attention to the structural and social causes of pain and addiction, which are critical to the design of the public health responses.

There are intuitive, causal connections between poor health and structural factors, such as poverty, lack of education and job opportunities, and poor health-care access, as well as substandard living and working conditions. Poverty and substance-use problems operate synergistically. For example, employment opportunities in lower-income communities sometimes are dominated by jobs with physical hazard, and lower-income households have less access to improved safety features of newer “smart vehicles.”

On-the-job acute and chronic injuries, and injuries from motor vehicle crashes, can give rise to chronic, painful conditions that can limit future employment opportunities, potentially resulting in a downward spiral of disability and poverty. The provision of necessary goods and services in our economy involves a certain risk of bodily harm. Reducing conditions that lead to chronic pain requires understanding how the risks of bodily harm are distributed in our society. These risks are not allocated at random; they flow along lines of class, race, gender and ethnicity.

On-the-job acute and chronic injuries, and injuries from motor vehicle crashes, can give rise to chronic, painful conditions that can limit future employment opportunities, potentially resulting in a downward spiral of disability and poverty. The provision of necessary goods and services in our economy involves a certain risk of bodily harm. Reducing conditions that lead to chronic pain requires understanding how the risks of bodily harm are distributed in our society. These risks are not allocated at random; they flow along lines of class, race, gender and ethnicity.

We tend to somaticize social disasters into physical pain, and the economic downturn and wars of recent years collectively have given rise to widespread social unease. For example, subjective economic hardship was associated with new-onset low back pain following the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011.

Intensifying substance use also may be a normal societal response to mass traumatic events, especially when compounded by income disadvantage. Increased binge drinking of alcohol was noted among U.S. Gulf Coast residents after hurricanes Katrina and Rita, with the greatest compensatory drinking among those with lower lifetime income trajectories; women experiencing work stressors after the terrorist attack on Sept. 11, 2001, were more likely to increase alcohol use. Heroin users in de-industrialized steel production areas of the Rust Belt cite economic hardship, social isolation and hopelessness as reasons for drug use, explicitly calling for jobs and community reinvestment to stem overdoses. Part of this relates to increased stress; part of it relates to disruption of social norms and controls. Until we understand the root causes of the opioid crisis, we will continue to fail in our efforts to turn its tide.

Q: How can we change the health-care delivery system?

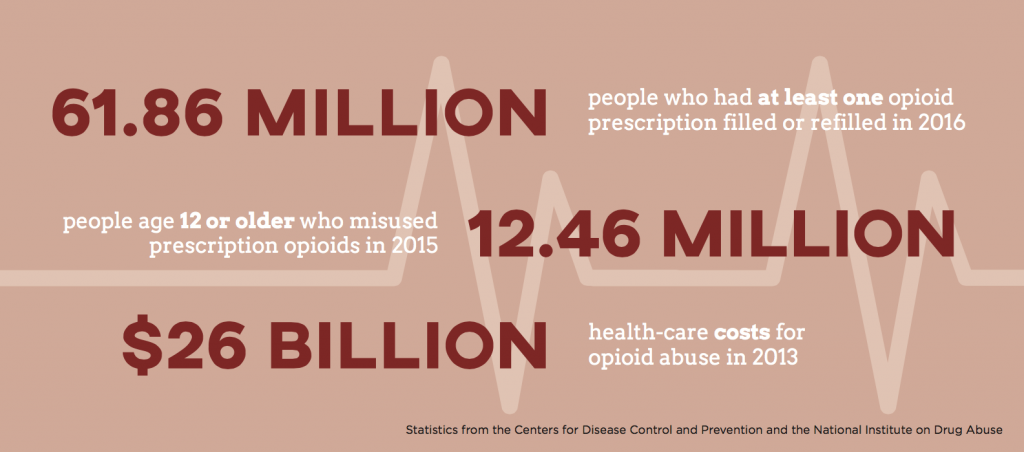

A: The observation that Canada and the U.S. have the highest per-capita opioid analgesic consumption in the world is central to the belief that these medicines are “overprescribed.” However, this word dangerously mashes together various prescribing behaviors, leading to the unrealistic expectation that reducing dispensing automatically, abruptly and proportionately will reduce overdose and abuse.

That has not happened. Opioid overdose death rates in the U.S. did not drop when opioid prescribing declined. The number of outpatient opioid analgesic prescriptions dropped 13 percent nationally between 2012 and 2015, yet the national overdose death rate surged 38 percent. Even ignoring the recent growth in heroin-related deaths, overdose deaths attributable to prescription opioids have not decreased proportional to dispensing. The term “overprescribing” hamstrings intervention innovation by singularly focusing on prescribing volume.

In practice, “overprescribing” can refer to starting doses, number of units in a single prescription, dosing schedules, potency, contraindications and other factors. A more rational approach would treat these as parallel but distinct issues. Yet, the legislative and clinical reaction has included proposals to bring dosage below arbitrary targets or abandon patients who do not conform to narrow expectations.

Institutional, legal and insurance architecture has robbed clinicians of time and incentives in busy primary-care settings to attend meaningfully to patients with overlapping pain and addictive disorders. Some providers struggle with their patients’ having complex, chronic medical conditions requiring regular follow-up, especially given limited recourse to non-therapeutic alternatives and the predominantly urban concentration of specialty services.

We urgently should adopt and pay for nonpharmacologic approaches to managing chronic pain – and we need to find ways to incentivize physicians to provide continued care of patients taking opioids to manage pain. For example, we might advance the concept of an “opioid well visit,” such that periodic checkups would be a reimbursed part of the course of opioid therapy. This would allow time for dose adjustment to minimize side effects and would afford the opportunity to discuss the more fundamental issues that gave rise to the pain in the first place.

At the same time, we should advance our health system’s capacity to deliver proven addiction treatment services, with medication-assisted treatment (for example, through methadone and buprenorphine), known as demand reduction. These therapies are supported by meta-analyses from extensive clinical trials and real-world practice. In France, for example, the opioid overdose epidemic was quelled by providing free, on-demand and ubiquitous drug treatment.

Waiting periods for limited treatment slots and limits on how many treatment episodes are covered by insurance are barriers we must address. We must actively refute pop-culture misconceptions about coercive forms of “treatment” that strip dignity from patients.

Q: Is there racial bias in our response to the opioid crisis?

A: Part of the alarm associated with the opioid crisis is that these drugs are reaching mainstream populations previously perceived as being nonusers. Conventional wisdom relegates heroin to the category of a long-standing, inner-city, urban problem. However, the increase in deaths from prescription opioids has deeply affected rural and suburban areas.

Recent studies have suggested that blaming the problem on too many prescriptions may result from implicit racial bias. The anecdotes about “accidental addicts” are emblematic of the mindset, in which anyone but a person of color must have become addicted inadvertently. When minorities have been involved, the periodic calls to action about drugs have framed drug use as a moral failing. We have spent decades pathologizing minority communities for turning to drugs to cope with social stressors and structural inequities. That these phenomena also may afflict rural and predominantly white communities is emerging as a new realization in public discourse.

The public discourse on heroin has been imbued with xenophobic undertones for more than a century. In the U.S., a new wave of overdose deaths from fentanyl, imported from overseas, has been observed recently. Fentanyl is a more potent opioid than is found in traditional street drugs. Rather than acknowledge and address the demand for heroin, the conversation has focused on cutting off the supply from foreign suppliers. Demand reduction, not supply reduction, should be the starting point for our response to the crisis.

We are at a crossroads in drug policy and national discourse on drug abuse. The silver lining that accompanies the body count of the opioid crisis is that it has accelerated the positive reframing of substance use as a medical issue, rather than a “character flaw.” We must be vigilant to ensure that the medicalization of addictive disorders does not fade when our current opioid crisis does; otherwise, we will do disservice to those who face chemical dependency in decades to come.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Leo Beletsky, associate professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University, and Dr. Dan Ciccarone, professor of family community medicine at University of California at San Francisco, in developing these concepts.

Portions of this article will be published in a forthcoming commentary in an academic journal.

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.