Pictures speak louder than words — at least on cigarette packs

December 1, 2016

Cigarette packaging has been a policy battleground ever since Congress enacted its first warning-label law in 1965. In recent years, researchers at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health have been in the thick of that battle.

In 2012, when a federal judge rejected the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s proposed new pictorial warnings on cigarette packs – which graphically depict blackened lungs and other frightening health consequences of smoking – he noted the lack of scientific evidence that such pictorial warnings reduce smoking.

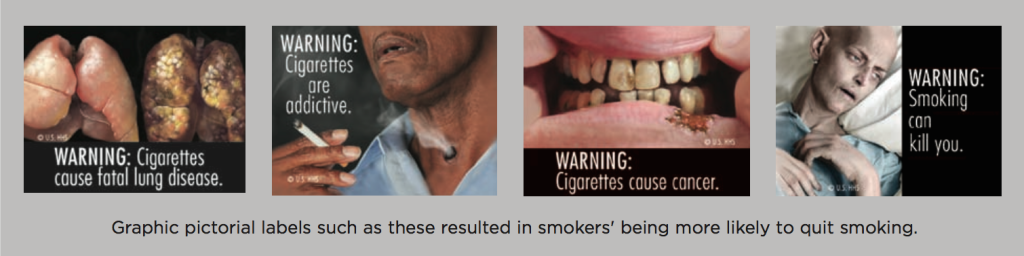

Noel Brewer, PhD, professor of health behavior, and colleagues at the Gillings School responded with a four-week clinical trial involving more than 2,000 smokers. They found statistically significant reductions in smoking behaviors among smokers whose cigarette packs had graphic images, compared to smokers whose packs did not. Exposure to pictorial warnings resulted in smokers’ being more likely to attempt to quit (40 percent vs. 34 percent) – and more likely to succeed in quitting (5.7 percent vs. 3.8 percent) – compared to those seeing text-only warning labels. The study was published in June 2016 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Noel Brewer, PhD, professor of health behavior, and colleagues at the Gillings School responded with a four-week clinical trial involving more than 2,000 smokers. They found statistically significant reductions in smoking behaviors among smokers whose cigarette packs had graphic images, compared to smokers whose packs did not. Exposure to pictorial warnings resulted in smokers’ being more likely to attempt to quit (40 percent vs. 34 percent) – and more likely to succeed in quitting (5.7 percent vs. 3.8 percent) – compared to those seeing text-only warning labels. The study was published in June 2016 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Our trial directly answers the court’s concerns by providing strong evidence that pictorial health warnings reduce smoking,” says Brewer.

Although the First Amendment and other issues make it harder for the government to require graphic warnings on cigarette packs in the U.S., at least 77 other countries already require such warnings. In Thailand, for example, pictorial warning labels have appeared on cigarette packs since 2005, and now cover 85 percent of the front of every cigarette pack and 90 percent of the back (see the Canadian Cancer Society’s 2014 international status report).

Brewer and his colleagues have concluded from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies in those countries that pictorial warning labels are indeed working – and are working better than text warnings.

“The findings from our reviews of scientific studies are broadly consistent with what we found in the clinical trial,” Brewer says. “By some estimates, pictorial warnings immediately reduce smoking by five percent, which is a big deal.”

“We think the case is closed – pictorial is superior to text,” says Kurt M. Ribisl, PhD, a professor of health behavior who is a former member of the FDA’s Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee and co-author of several of the pictorial warning studies.

The FDA is expected to issue a new set of proposed pictorial warning labels within the next year or two. If the tobacco companies sue again, the recent clinical trial findings by Brewer, Ribisl and colleagues could be an important factor in withstanding the challenge.

“The UNC team has provided key evidence that will inform the policy debate,” says Ribisl. Gillings School researchers have been active in shaping another new – and perhaps harder-to-challenge – anti-tobacco strategy, enabled by the same 2009 legislation that mandated cigarette pack pictorial warnings. In that law, Congress also gave the FDA leeway to require disclosure on cigarette packs – most likely on the sides – of some of the more harmful chemicals in tobacco smoke.

“People, including smokers, are largely unaware of the chemicals in cigarette smoke, but they’re interested in learning about them,” says Marcella H. Boynton, PhD, research assistant professor of health behavior, summing up a national survey that she and her colleagues, including Ribisl and Brewer, published in BMC Public Health in June 2016.

That finding will help maintain pressure on the FDA to issue a new rule in this area, but it is not yet clear how best to present such information on the side of a cigarette pack. Cigarette smoke contains thousands of distinct chemicals, of which more than 100 – including arsenic, benzene, cadmium, and polonium 210 – are established toxins and/or carcinogens. Which ones should be highlighted and how their health impacts should be explained are issues yet to be resolved.

Dr. Marcy Boynton (Photo by Jennie Saia)

“Which constituent message best discourages smoking?” asks Boynton. “Saying that a toxin in cigarette smoke causes bladder cancer, or that it’s found in rat poison? These are the kinds of questions we’re wrestling with.”

One concern is that cigarette companies could use constituent messages to imply that some cigarettes are relatively harmless – as they formerly did with the now-banned “low tar” designation.

“We don’t want consumers to look at the label and decide, ‘Oh, this has less arsenic; it must be safer,’” Boynton says.

What is needed, she adds, is a systematic approach to understanding which types of constituent-related messages are most efficient at conveying health risks.

“That’s what our work is now mostly focused on,” she says.

Given clear health risks associated with smoking, it might seem odd that governments do not ban cigarettes. As Ribisl points out, however, making cigarettes illegal would criminalize the behavior of more than 40 million tobacco users in the U.S. and encourage a vast black market. Thus, the fight against tobacco remains largely a fight to coax smokers away from their health hazard of choice – and doing that with product packaging remains a favored strategy.

“A pack-a-day smoker gets 20 impressions of label messages per day, which is 7,300 impressions a year,” says Ribisl. “The cigarette package is an extremely low-cost and effective venue for discouraging tobacco use.”

“A pack-a-day smoker gets 20 impressions of label messages per day, which is 7,300 impressions a year,” says Ribisl. “The cigarette package is an extremely low-cost and effective venue for discouraging tobacco use.”

Good news came on Oct. 4, 2016, in the form of eight anti-tobacco groups’ suing to force the FDA to require graphic cigarette package warnings, as mandated by law. (For more information, see tinyurl.com/FDA-tobacco-suit).

“Our findings will help change national policy,” Brewer says. “Now the FDA can require graphic warnings and successfully defend that action in court. Implementing graphic warnings will save hundreds of thousands of lives.”

— James Schnabel

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.