Perspectives on the flu: David Weber, MD, MPH

May 15, 2018

Q: How did you become interested in hospital preparedness and response?

Q: How did you become interested in hospital preparedness and response?

A: I have always been fascinated with how and why new infectious agents emerge – like the Black Plague in the Middle Ages and the 1918 influenza pandemic – and how to control the infectious outbreaks that have devastated human populations.

During my 33 years here at UNC, I have chaired UNC Hospitals’ working groups that responded to the 2001 anthrax attack in the United States, the 2002–2003 SARS [severe acute respiratory syndrome] outbreak, the 2009 pandemic influenza, the MERS [Middle East respiratory syndrome] outbreak in the Middle East, the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in Africa, and Zika in the Americas.

Q: Do we know how the 1918 flu became such a killer strain?

A: Every year, influenza kills between approximately 300,000 and 650,000 people. Periodically, the virus shifts to a new strain for which humans do not have any pre-existent immunity. The 1918 flu represented such a pandemic

The high number of deaths resulted from many factors – a new pandemic strain, high infectivity, high pathogenicity and rapid worldwide transmission, due, in part, to World War I, improved transportation that resulted in greater mobility and the growth of cities.

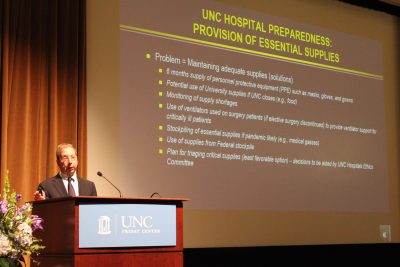

Hospitals need a six-months’ supply of gowns, gloves, masks and respirators to be ready for an epidemic of flu. UNC Hospitals has that available, thanks in part to Dr. David Weber’s advocacy.

Q: How big a problem is influenza in 2018?

A: In the U.S. alone, influenza causes between 9 million and 35 million infections per year, resulting in 140,000–710,000 hospitalizations and approximately 12,000–56,000 deaths. While people at the extremes of life (very young or very old) or with underlying co-morbidities are at the highest risk for death, even young and healthy people die of influenza.

Q: Could a pandemic on the same scale as the 1918 pandemic happen again?

A: The question is not whether we will experience another pandemic – but when. Given the global nature of transportation, a pandemic likely will spread rapidly. We have the ability to develop a flu vaccine, but vaccine development takes at least four to six months, and we have antivirals to treat influenza, but we may exhaust the supply. As a society, we must remain vigilant and prepared.

Q: What are some best practices currently used in hospital settings?

A: Given that a flu pandemic could result in millions of people in the U.S. developing illnesses and tens of thousands dying, all health care facilities must have a well-developed plan for managing a surge of ill patients.

To do this, we need to improve outpatient facilities, dramatically increase clinics’ ability to evaluate patients who may have influenza, increase the number of inpatient beds to care for patients, and increase the number of ventilators available.

Dr. David Weber speaks at the Gillings School’s Going Viral symposium on April 5. (Photo by Jennie Saia)

We also must increase the number of health care providers available to care for patients. To achieve this, we need to move toward shifts in which health care providers work 12 hours on and 12 hours off. In a crisis, we also can recruit nursing and medical students (under the supervision of fully trained health care providers), retired nurses and physicians, and health care providers from professional schools. For example, we could recruit pharmacists in the School of Pharmacy or nurses and physicians in the epidemiology department to provide health care to patients.

We should increase the numbers of health care personnel available for patient care by providing these personnel with prophylactic antivirals and rapidly testing health care workers who are ill so we can identify and exclude workers who might spread the flu.

We need laboratories that can develop diagnostic tests for new strains of influenza and perform large numbers of tests rapidly.

Finally, we can ensure that there is a six-months’ supply of masks, respirators, gloves and gowns to protect our health care personnel, as well as food and sleeping areas for those who will be providing patient care. We have that available at UNC Hospitals.

Q: What other work must be done?

Q: What other work must be done?

A: Despite great success in preventing infections with safe drinking water and vaccines, and treating infectious illnesses with antibiotics and anti-infectives, we continue to see outbreaks and the emergence of new infectious diseases.

For the future, we need to be developing a universal influenza vaccine; shortening the time for development of new influenza vaccines; stockpiling antivirals; and expanding public health personnel and resources.

Fortunately, new technologies will allow us to speed vaccine development, and we are already on our way to developing a universal influenza vaccine.

—Amy Strong

David Jay Weber, MD, MPH, is professor of epidemiology at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, professor of medicine and pediatrics in the UNC School of Medicine, and director of hospital epidemiology (infection control) at UNC Health Care. His research has focused upon health care-associated infections, antibiotic stewardship, new and emerging diseases, and vaccine implementation.

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.