Marking the centennial of the 1918 pandemic flu

May 15, 2018

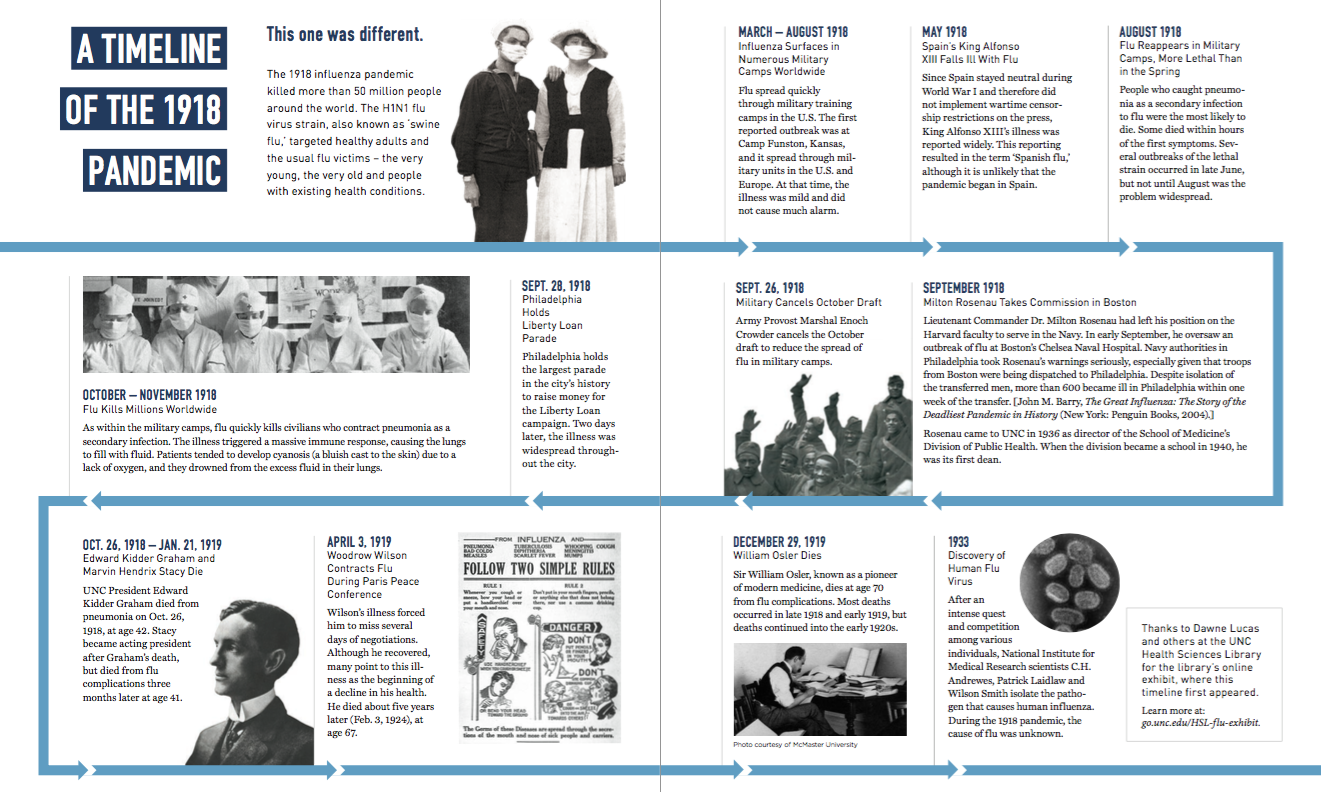

A century ago, “Spanish flu” swept the United States and world in the most aggressively lethal disease outbreak in human history. Spreading fast and killing quickly, the 1918-1919 global influenza pandemic stole the lives of nearly 700,000 Americans, among them, in 12 weeks’ time, two successive presidents of the University of North Carolina.

Its cause, an H1N1 flu variant of unprecedented virulence, was then beyond scientific understanding. In little more than 18 months, this flu infected half of the world’s 1.5 billion people and killed 50 to 100 million. Modern demographers, citing improved pandemic mortality models, tell us that this haunting estimate, in fact, may be too low.

Unfolding against the backdrop of World War I, the pandemic – called “Spanish flu” because Spain, a noncombatant nation, took no steps to censor popular news reports of the spreading illness – may have appeared first in military camps in northern France in 1916, emerging from a mix of swine and poultry influenzas and jumping species to infect soldiers.

A first wave of pandemic sickness in early 1918 was relatively mild, but a further mutation yielded the deadly second wave in fall of that year – and another in early 1919. No corner of the world was spared, as the disease traveled handily with anyone infected.

A Red Cross nurse draws water at a military camp in Brookline, Mass., in 1918. (Photo courtesy of U.S. National Archives)

Healthy young adults, who rarely die from common infectious diseases, became casualties, along with older adults and children. Death often was fast and terrible. Patients drowned as their lungs filled rapidly with fluid, their faces turning blue, for lack of oxygen.

President Woodrow Wilson, incapacitated by flu at the Paris Peace Conference, lost his chance to assert his vision for just settlement terms among belligerents and new, supranational mechanisms, such as a League of Nations, which might ensure future world peace.

It could happen again

Could a similar catastrophe happen in 2020?

Insistently and emphatically, experts say yes, future global infectious pandemics are a question of when, not whether.

Recent pandemic scares – Avian flu, SARS, Ebola, Zika and others – reveal terrifying limitations of our global capacity to respond quickly and effectively. Should a novel, aggressively virulent and contagious influenza variant emerge, the global community might be easily overwhelmed.

Throughout winter and early spring 2018, hospitals in the United States screened those suffering from H3N2 seasonal flu in tents erected hurriedly in their parking lots, having overrun the capacity of their emergency departments. The sobering fact is that H3N2, though virulent, is the palest cousin of the 1918 flu. Despite these realities, our political leaders now propose sharp funding cuts to the Global Health Security Initiative. Scientists, meanwhile, continue to seek a universal flu vaccine and to develop more effective antivirals.

The Gillings School’s Symposium

People without protective masks could not board a Seattle trolley car in 1918. (Photo courtesy of U.S. National Archives)

In early April, the UNC-Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health co-hosted Going Viral: Impact and Implications of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, a gathering that aimed to define the “state of the science” in the study of pandemic infectious diseases, specifically influenza.

Interdisciplinary experts, some of whose comments are included in the following pages, discussed the risks, latest science and best practices to prevent, prepare for and respond to an infectious disease pandemic.

Going Viral was the product of a powerful partnership led by the Gillings School. Symposium co-sponsors included UNC’s Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, RTI International, UNC Libraries and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. The efforts of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History will maximize public education and engagement.

“Uncontrolled infectious disease outbreaks can cost millions of lives and tens of billions of dollars,” said Barbara K. Rimer, DrPH, dean of the Gillings School. “They can move fast with modern air travel, as SARS and Ebola showed. If we have neither the means to prevent nor treat, as is sometimes the case, even in developed nations, the impact could be catastrophic. This is even more true if public health infrastructure is not robust.”

Rimer noted that the responsibility of public health leaders is to minimize the potential for worst-case scenarios to occur.

“As I read about the 1918 influenza pandemic,” she says, “I realized I had never known how deadly it was, how many mistakes were made, even with what was known at the time, and how the entire world could be upended by a terrible health crisis.”

As Rimer asked questions of others, she says, she was stunned by how little even knowledgeable health professionals knew about the events surrounding 1918.

“I thought we could learn a huge amount to help us in the future by examining the 1918 influenza pandemic from an interdisciplinary perspective,” she says, “bringing to bear history, virology, literature, epidemiology, medicine and other fields to look backward with an eye to the future. The issues are intensely local and deeply global. Flu is a health concern issue that crosses all disciplines, and we were thrilled at the high levels of engagement from across our campus.”

“I thought we could learn a huge amount to help us in the future by examining the 1918 influenza pandemic from an interdisciplinary perspective,” she says, “bringing to bear history, virology, literature, epidemiology, medicine and other fields to look backward with an eye to the future. The issues are intensely local and deeply global. Flu is a health concern issue that crosses all disciplines, and we were thrilled at the high levels of engagement from across our campus.”

Gina Kolata, renowned science reporter for The New York Times and author of the best-selling Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It, gave the keynote address, which also served as the 2018 Fred T. Foard Jr. Memorial Lecture.

—Joe Mosnier

Learn more about the 1918 pandemic

sph.unc.edu/1918flu

Read about the Gillings School’s flu symposium, held April 4–6 in Chapel Hill, N.C.

tinyurl.com/WUNC-baric-on-flu

On April 4, Gillings School epidemiology professor Dr. Ralph Baric and UNC history professor Dr. James Leloudis were interviewed by WUNC’s “The State of Things” about the 1918 flu pandemic.

go.unc.edu/gazette-flu-symposium

UNC’s University Gazette posted an article to mark the centennial of the pandemic and announce the Gillings School’s symposium.

influenzaarchive.org

Dr. Howard Markel, a medical historian from the University of Michigan, spoke at the Gillings School’s flu symposium on April 5. Markel is co-editor-in-chief of the Influenza Encyclopedia: A Digital Encyclopedia of the American Influenza Epidemic of 1918–1919.

go.unc.edu/mondaymorning-flublog1

go.unc.edu/mondaymorning-flublog2

Read Dean Barbara K. Rimer’s blogs about the 1918 flu and the Gillings School’s symposium.

tinyurl.com/smithsonian-1918-flu

“The Next Pandemic,” featured here in Smithsonian magazine, is an exhibit organized in collaboration between the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

sph.unc.edu/going-viral/video

See video from the Gillings School’s Going Viral symposium.

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.