The way we were

December 1, 2014

Jo Anne Earp, ScD,

Retired professor and chair, health behavior

When I arrived at the School in 1974:

Gillings was the name of an assistant professor in biostatistics, not the name of the School, and Greenberg was the name of the dean, not a building. Our one building, Rosenau Hall, had a very convenient parking lot where the Michael Hooker Research Center was built.

There were 17 schools of public health in the country, not more than 50 as there are now.

Smoking was allowed in all offices, and many faculty members smoked at this school and others.

All department chairs were men, with the exception of the Department of Public Health Nursing.

The N.C. Institute for Public Health didn’t exist; all faculty members were required to teach a certain number of continuing education credits each year.

There were no personal computers — only a mainframe for the School.

When I arrived in the Department of Health Behavior:

I was a research associate, promoted when I began to head the doctoral program one year later, then promoted to research assistant professor and eventually (1977) to assistant professor.

Our MPH program was only 18 months long, and was headed by Leonard Dawson, MSPH, graduate of the Department of Health Education, under Dr. Lucy Morgan, who was the first chair. MPH cohorts had 25-35 students (compared to 50-55 now), with 10-12 faculty members to teach them (now more than 25 faculty members).

Dr. Guy Steuart was department chair, Dr. Godfrey Hochbaum a full professor, Leonard an assistant professor and John Hatch a doctoral student (later a faculty member). I was the first woman, after the Lucy Morgan era.

We had no bachelor’s programs. One was eventually added in health behavior and lasted for about a decade through the interest of Harriet Barr, Ethel Jackson and John Hatch.

There were no scholarships for health behavior students. Bill and Ida Friday anonymously funded the Lucy Morgan fellowships in honor of Ida’s having studied health education here. In the beginning, we gave one small Lucy Morgan fellowship, at less than half the level we give now for each of three.

—Dr. Jo Anne Earp

Earp, recently retired, was appointed professor in 1992. She served as chair of the health behavior department from 1996 to 2005, and again from 2009 to 2012. She was interim chair from 2008 to 2009. She still teaches and conducts research in phased retirement.

C. M. Suchindran, PhD

Professor of biostatistics

I arrived in Chapel Hill from India on Labor Day 1967 as a newly admitted student in the Department of Biostatistics’ MSPH degree program. During a two-week orientation, we visited a number of rural-area health departments in N.C. to gain first-hand knowledge about public health activities in the state. For a person whose studies had focused on mathematics and statistics, this field experience and a 10-week practicum in the Washington, D.C., health department were great eye-openers.

After successful completion of the master’s program, I was admitted to the doctoral program. At that time, it was quite new, having formally begun in fall 1965. The program allowed me to specialize in demography.

A number of career-enhancing personal events took place early in my doctoral training, including the invitation to work with Dr. Mindel Sheps. Her personal attention helped to build my research career. I was also fortunate to learn from Dr. [Bernard] Greenberg the art of teaching biostatistics, a skill he emphasized and valued.

In the late 1960s, the School’s student body included many international students from India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Vietnam and elsewhere, and interactions with them offered great lessons in global health. One pleasant memory is of international students’ yearly visit to the home of Dean Fred Mayes and his wife, Dorothy, for dinner.

I was fortunate to receive an offer to join the faculty when I completed my doctorate in 1972. My initial challenge was to build a strong demography training program in the department. The International Program for Laboratories for Population Statistics (POPLAB), established in 1969 with funding from USAID, grew considerably during this time by attracting prominent researchers in the field to work for the program, including Dr. Dan Horvitz, now senior vice president of RTI, and Dr. Dick Bilsborrow, now research professor of biostatistics.

Dr. Suchindran (far right) poses with other international students in 1970. Dr. Bernard Greenberg (fourth from left) was biostatistics chair at the time.

The biostatistics department received one National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant in 1971 to train biostatisticians in population studies and another for “Measurement methods for population change.” The department’s success in winning the latter highly competitive grant enhanced opportunities for faculty members and students. Drs. Greenberg, Jim Abernathy, Bradley Wells, Mindel Sheps and Gary Koch led auxiliary projects. My part in the project, under the direction of Dr. Sheps, involved work in the area of models for human reproduction. My significant achievement as a population researcher is that, under my leadership, the population statistics training program received continuous NIH funding for 35 years. This success allowed the department to recruit highly qualified students to the doctoral program.

Significant changes at the Carolina Population Center (CPC) shaped population research on campus. The public health school’s training and research in population studies also were enhanced by the addition of prominent researchers including Dick Udry and Jerry Hulka (maternal and child health), Abdul Omran (epidemiology) and Sagar Jain (health policy and management), to name a few. I became a CPC fellow and, with Professor David Guilkey (economics), established a CPC statistical services core to improve population researchers’ analytical skills. The core received continued NIH support from the time of its establishment in 1984.

It is gratifying to know that many well-established population centers followed our example in forming a statistical services core. Through the UNC core, I was able to interact with faculty members Schoolwide to win federal research grants. I also helped train population researchers in these departments. These activities resulted in my serving more than 75 students at the School in their doctoral research. Through these activities, I feel I helped train the future generation of population researchers — one of the primary goals in my career.

—Dr. C. M. Suchindran

Read more about the POPLAB at tinyurl.com/RSS-Poplab.

Pranab K. Sen, PhD

Cary C. Boshamer Distinguished Professor of biostatistics

In fall 2015, Dr. Pranab K. Sen, Cary C. Boshamer Distinguished Professor of biostatistics, will celebrate 50 years of service on the biostatistics faculty at The University of North Carolina’s public health school.

An interview about his life is transcribed in a 2008 issue of the Journal Statistical Science (23:4, pages 548-564). See tinyurl.com/2008-Sen-interview.

Even after I came to Chapel Hill in fall 1965, I had not decided whether I should stay for a long time or go back to Calcutta. I remember during the three years (1964–1967) when I was on leave from Calcutta, I used to write both my affiliations on all my publications. Some Chapel Hill colleagues asked me whether I was serious about continuing this dual affiliation. I had to defend myself — Calcutta University was my home, and I couldn’t give it up.

Eventually, I realized that UNC was one of the best places for statistics in America, if not the world, and by being here I could not only strengthen my background but develop additional ties with Indian schools. In this way, UNC induced me to settle in Chapel Hill, despite offers from other universities over the years.

—Dr. P.K. Sen

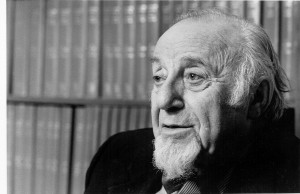

Cecil G. Sheps, MD, MPH

Founder and first director of the UNC Health Services Research Center

Cecil G. Sheps, MD, MPH (1913–2004), was a founder and first director of the UNC Health Services Research Center, which was renamed in his honor in 1991.

Sheps was born in Winnipeg, Canada, where he received a medical degree from the University of Manitoba in 1936. As a member of the Saskatchewan Department of Public Health from 1944 to 1946, he played a major role in the development of universal medical and hospitalization insurance. He earned a Master of Public Health degree from Yale University in 1947, after which he became director of program planning in the division of health affairs and research professor of health planning at UNC-Chapel Hill, perhaps the first in the U.S. to hold such a title.

In 1953, he became general director of Beth Israel Hospital (Boston) and professor at Harvard Medical School. In 1965, he was named director of Beth Israel Medical Center in New York and taught at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Upon returning to UNC in 1968, Sheps founded UNC’s health services research center and soon became vice chancellor for health affairs. Six years later, he left that position to devote himself to being professor of social medicine and epidemiology in UNC’s schools of medicine and public health. In 1980, he was appointed Taylor Grandy Distinguished Professor.

Sheps was a founding member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences and member of the New York Academy of Medicine.

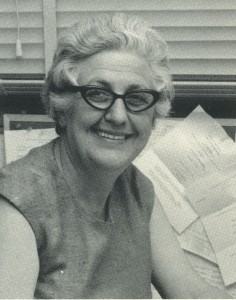

Mindel Cherniack Sheps, MD, MPH, (1913–1973)

Former biostatistics professor

This article is compressed from a biographical entry in The Jewish Women’s Archive Encyclopedia, written by Cecil G. Sheps and Sam Sheps, son of Mindel and Cecil. Read more at tinyurl.com/mindel-sheps-bio.

—Dr. Mindel Sheps

As a physician, biostatistician and demographer, Mindel Cherniack Sheps was acutely aware of the role science could play as a powerful social force. She taught that peace, social justice and science were inextricably bound.

She was one of the few Jewish women admitted, under a strict quota system, to medical school at the University of Manitoba, graduating in 1936. She received a master’s degree in public health from the University of North Carolina in 1950 and an honorary Doctor of Science degree from the University of Manitoba in 1971.

She married Cecil George Sheps in 1937. As a resident at the Children’s Hospital in Winnipeg in 1937, she became aware of the social issues underlying maternal and child health. In 1938, she and her husband went to London, where she worked at the Marie Curie Hospital in Whitechapel, further observing the effects of poverty on health.

In 1944, Sheps became secretary to the Health Commission in Saskatchewan. In this position, she surveyed hospital services and strongly supported the hospital insurance scheme enacted in 1945, the first in North America, giving political expression to her experiences and leading her toward a broader vision of epidemiology and the social factors influencing the health of individuals and populations. In this vision, she was supported by her husband, who also was trained in public health, health administration and health services research.

Further training in public health established Sheps as a leading thinker in the fields of statistics and demography. She held academic positions at the University of North Carolina, Columbia University, and the University of Pittsburgh.

While trained in mathematics and biostatistics, Sheps was largely self-taught in demography, publishing in that field almost exclusively after 1963 and achieving an international reputation. Her interest in demography stemmed from a strong social conscience, from her experience in the 1940s as a physician, school board member, and particularly from the struggle of Planned Parenthood for recognition in Winnipeg. She was intellectually stimulated by biostatistical applications in demography, and a critical element of her work was her recognition of the links among poverty, fundamental social inequality and population growth.

For Sheps, demography became a science that could achieve social justice and clarify issues of women’s rights and equality. Her statistical and demographic research was innovative and insightful, founded on solid mathematical principles; however, it was the social application of this knowledge that she believed to be crucial.

John Anderson, PhD

Professor emeritus of nutrition

The old Phipps House at 315 Pittsboro Street (named for a local judge) served as the home of the nutrition department from 1972 until the McGavran-Greenberg building was constructed in the mid-1980s. The Phipps House was razed soon thereafter for the new building that houses the School of Social Work (Tate-Turner-Kuralt).

In spring 1972, while I was a visiting professor in orthopedics, I gave a few lectures on nutrients for a required Master of Public Health course. Subsequently, I joined the nutrition department as a faculty member.

Despite limited space and laboratories, the department launched two new academic programs in 1975, the first a nutrition BSPH degree that was part of a schoolwide program for undergraduates, and the second, a DrPH program that focused on applied research projects that benefited North Carolina and the nation.

When we moved from the Phipps House and Rosenau Hall to our new home on the second floor of McGavran-Greenberg, our space was ample for the first time in many years. The new laboratories and other facilities permitted the expansion of faculty members in both nutritional biochemistry and public health nutrition.

In 1984, Dr. John Anderson gave a talk in Krasnodar, Russia (then the U.S.S.R.) about the impact of diet upon chronic diseases.

The doctoral program, first offered around 1992, provided more opportunities for basic nutrition investigations in the three newly defined divisions in nutrition — nutritional biochemistry, applied and public health nutrition, and nutritional epidemiology. An influx of new faculty researchers and federal funds has propelled the department into a national and international leadership position that attracts outstanding students.

Of course, when the Michael Hooker Research Center opened in 2005, its state-of-the-art laboratories included 20,000 square feet dedicated to nutrition research.

—John Anderson, PhD

Anderson, professor emeritus of nutrition at the Gillings School and past president of the American College of Nutrition, has written more than 150 peer-reviewed journal articles and co-authored several books, his most recent about the cardiovascular benefits of the Mediterranean diet. He has had a long research career in the field of calcium and bone metabolism.

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.