The great unsweetening

December 1, 2016

What explains this sudden shift toward health? Many say it is the result of a tax – a 10 percent excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) – which became law in Mexico in January 2014. That the tax became policy owes much to the work of Barry M. Popkin, PhD, W.R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor of nutrition and director of UNC’s Global Food Research Program, and to his collaboration with the Mexican National Institute of Public Health (INSP) and key nongovernmental organizations.

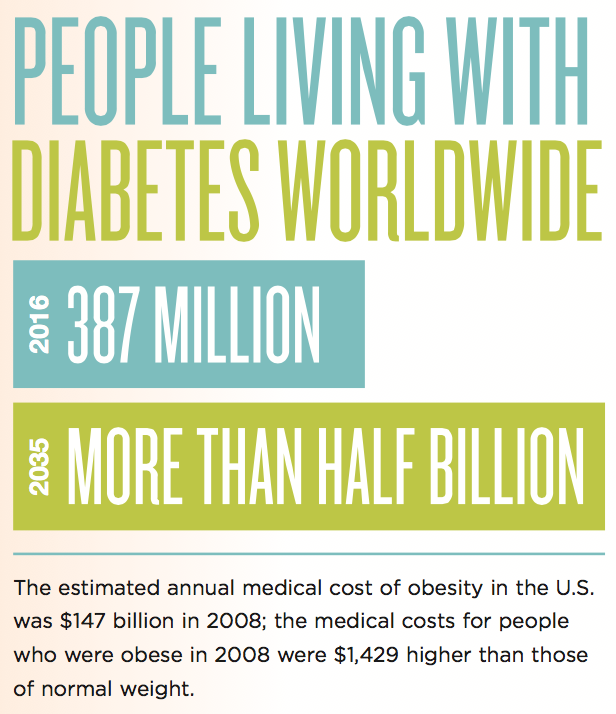

In 2006, Mexican minister of health José Ángel Córdova, undersecretary of health Mauricio Hernández and INSP nutrition expert Juan Rivera, PhD, invited Popkin to Mexico City to discuss ways to combat the country’s epidemic of obesity and related Type 2 diabetes. The statistics were astounding. Since 2000, the prevalence of diabetes in the country had doubled, and about one third of 5- to 11-year-olds were overweight or obese.

Epidemiologists already had linked obesity to sugary sodas and other empty-calorie drinks, the consumption of which was skyrocketing in Mexico. Rivera and Hernández wanted to do something to curb the country’s addiction to these drinks.

Popkin helped set up a Mexican beverage guidance panel – a team of eminent academics to advise on the public health aspects of common beverages – such as the one he had established in the United States in 2005. (See tinyurl.com/US-beverage-panel.) That panel then published a report summarizing the state of the science regarding the impact of SSBs upon health.

Popkin helped set up a Mexican beverage guidance panel – a team of eminent academics to advise on the public health aspects of common beverages – such as the one he had established in the United States in 2005. (See tinyurl.com/US-beverage-panel.) That panel then published a report summarizing the state of the science regarding the impact of SSBs upon health.

“We used that document to create awareness and public debate and attempted to create a consensus among Mexican academics,” Popkin says. “That was a major step before the government pushed to establish an SSB tax.”

The push met with resistance. Coca-Cola and other soda companies held long-standing influence in Mexican policy-making circles; the previous Mexican president, Vicente Fox, once had been chief of Coca-Cola Mexico. However, in late 2013, a 10 percent SSB tax – negotiated from the 20 percent originally proposed – was at last signed into law, becoming effective in January 2014.

What was the result? During the first year of the tax, the rate at which Mexicans purchased taxed SSBs began to decline sharply, reaching a 12 percent reduction (22 mL fewer per person, per day) by December, and averaging a 6 percent drop in purchases over the entire year. Low-income Mexicans, who would be expected to be more sensitive to price increases, reduced their purchases the most, by 9 percent over the year, and in that sense, received the greatest benefit. Meanwhile, purchases of untaxed beverages, such as water, rose by comparison.

Dr. Barry Popkin (Photo by Linda Kastleman)

Dr. Shu Wen Ng (Photo by Elisabeth Delafield)

The study, published in BMJ in January 2016 as the first of many planned evaluations of the tax’s impact, was co-authored by M. Arantxa Colchero, PhD, researcher at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health; Rivera, her colleague at the INSP; Shu Wen Ng, PhD, research associate professor of nutrition at the Gillings School; and Popkin.

The apparent success in Mexico has helped inspire a global awakening among policy makers about the public health costs of sugary, low-nutrition drinks and foods. Chile began applying its own countrywide 8 percent SSB tax in 2015. Popkin expects South Africa to follow with a 20 percent tax in 2017, along with Colombia, whose government has been consulting him for two years.

Popkin says that his team is now working at the ministerial level with about a half-dozen other governments to help them implement sugary drink taxes and related policies, and he himself is directly aiding several more.

Dr. Barry Popkin (at right, holding child) visits with a family in their home in Chiapas, Mexico. (Contributed photo)

“We’re very much in the center of this issue,” he says. Oddly enough, one of the countries in which the SSB- tax movement has been slow to gain traction is the U.S., where “Big Soda” interests typically condemn such efforts as “grocery taxes.” Prior to fall 2016, only two U.S. cities, Berkeley and Philadelphia, had managed to pass local SSB taxes. A study by Popkin, Ng and colleagues, evaluating Berkeley’s tax, likely will be published next year and could help encourage other cities to follow suit.

Certainly, the movement is still alive in America. “Five local governments passed sugary drink taxes during November elections – Boulder, Oakland, San Francisco, Albany, Calif., and Cook County, Ill.,” says Ng.

Of course, sugary drinks are not the only dietary contributors to obesity. One of the next frontiers for Ng, Popkin and their colleagues are taxes aimed at junk food; such a tax was imposed in Mexico at the same time as the SSB tax. The UNC and INSP teams jointly are studying its impact on spending and health.

“These types of policies have been talked about for a long time, but there’s growing momentum for them now, and I think they’re really going to make a difference,” Ng says.

– James Schnabel

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.

Save