Can good nutrition reduce risks for chronic diseases?

October 15, 2017

Alice Ammerman, DrPH

Mildred Kaufman Distinguished Professor of Nutrition

Director, UNC Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

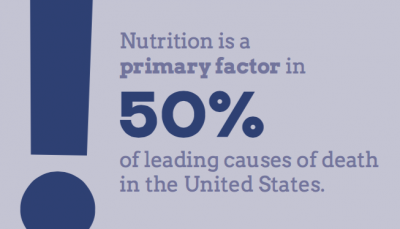

Nutrition is a primary factor in five of the diet are contributory, and they often have a combined top 10 leading causes of death in the United States.

It’s telling that immigrants who come to this country and adopt a “western diet” often see their rates of chronic disease increase dramatically. What’s more, nutrition-related health problems such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes have been linked for some time with racial, ethnic, economic and geographic disparities in our country.

Q: Who is at greatest risk for a nutrition-related illness?

A: Nationally, the highest rates of nutrition- related chronic diseases are found among African-Americans, Hispanics and Latinos/Latinas, particularly among those with the lowest incomes and those who live in rural areas. The southern states generally have the highest incidence of chronic diseases, and experts often refer to the southeastern U.S. as the “stroke belt,” where rates of hypertension and stroke are two to three times the national average.

While we haven’t identified all the causes of chronic disease disparities, we know that both poverty and effect. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.” The lack of that access is what we call “food insecurity.”

While we haven’t identified all the causes of chronic disease disparities, we know that both poverty and effect. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.” The lack of that access is what we call “food insecurity.”

It may sound counterintuitive, but many people in the U.S. suffer from both food insecurity and obesity. Many of the least-expensive foods available are very high in sugar, refined carbohydrates and low-quality fats, which all contribute to poor nutritional health and obesity. While it is possible to eat a healthy diet on a budget, doing so requires significant knowledge, time and food preparation skills.

Most researchers and nutritionists are now quite confident that the strongest evidence upholds the benefits of the Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes more high-quality fats (vegetable/olive oils and nuts), whole grains, and fruits and vegetables. One focus of my work is adapting this premise to the southern palate and local food availability. I refer to this hybrid as the “Med-South diet.”

Q: What can policy do to help improve nutrition?

A: Food policy can impact people’s diets at the local, national and global levels. On a very local scale, workplace policies can be put in place to encourage providing healthier options for celebrations and lunch meetings. At the Gillings School, the dean’s office does not serve sugary soft drinks, and healthy, local foods generally are provided at Schoolwide events.

On the state level, one positive example is the recently passed bill in North Carolina that provides funding to corner stores in food deserts so they can purchase refrigeration equipment that facilitates the sale of fresh and frozen produce.

Dr. Alice Ammerman prepares to purchase produce at the Carrboro (N.C.) Farmers Market. (Photo by Linda Kastleman)

At the national level, the U.S. Farm Bill contains many important nutrition benefit programs, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as Food Stamps) and assorted Child Nutrition Programs (including ones that provide school breakfasts and lunches and summer meals for children). These programs increase access to healthy food among those with limited incomes.

Globally, some countries have instituted national taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages. Such taxes have curtailed the consumption of these obesogenic products while generating funding for public health programs.

Q: How can changes in the food system make a difference?

A: Another approach to improving nutrition is by making conscientious changes to our food choices and food system. By consuming locally and sustainably grown food, we can reduce toxic exposures from pesticides and fertilizers while revitalizing our Dr. Alice Ammerman prepares to purchase produce at the Carrboro (N.C.) Farmers Market. connection to the source of our food. By shopping at farmers markets or joining a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program, through which a box of farm-fresh produce is delivered each week, consumers can reconnect with what it means to “eat with the seasons” and rekindle the social and creative aspects of cooking together and sharing meals.

On the positive side, “eating local” is increasingly popular, and federal nutrition programs are being adapted to facilitate the use of food benefits at farmers markets and through CSAs. While it can be a challenge to assure simultaneously that farmers get a fair return on investment and consumers have access to affordable healthy food, innovative strategies are making this more possible.

Sharing food should be a wonderful and joyous occasion. My work aims to ensure that making healthier choices – and supporting local farmers in the process – adds to that satisfaction, and ultimately, improves our collective health.

Carolina Public Health is a publication of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. To view previous issues, please visit sph.unc.edu/cph.